Women are too emotional to be good leaders.

Surely you’ve heard this statement before—or, more likely, you’ve heard other statements or seen other behavior that is less blatant but still stupidly sexist. It’s a misconception that’s played with in the latest installation of the Marvel Universe saga—Captain Marvel, staring Brie Larson, Samuel L. Jackson, Jude Law, and a cat (four cats, actually) named Goose.

From a classic film studies/film critiquing perspective, Captain Marvel is mediocre. Uneven or lacking characterization, visuals that rely too much on CGI to be compelling, a storyline chocked full of plot holes and vague themes. But to be honest, these critiques could be applied to most of the Marvel Universe films. In fact, it has almost become a staple ingredient of their formula—an in-joke of what the strong of MU movies are. They revel in their seeming flaws. They allow themselves space to have fun, to be for the present rather than worrying about posterity.

And, the quality of a MU movie can’t be decided by an individual film alone. Rather, more important than individual characterization or plot arc is taking into consideration the system of films as a whole. Each MU film is judged by how it fits with the other films in the network of MU films, and how it fits with (or complicates) its current cultural context. It relies on references, cultural symbols the target audience will understand. These films are Events, first and foremost. They can’t be judged in quite the same way as an indie film that premiers at Sundance.

Under these qualifications, Captain Marvel soars. You can’t separate it from its context as an event—it is a teaser for what we’re all waiting for, Avengers: Endgame, the afterword to Thanos’s gut-wrenching upset victory. We’re waiting for the good guys to win again. We’re waiting for reasons to root for the good in the face of so much chaos and hate.

Captain Marvel gives us the crumb that whets our appetite. Like the serials of yore that used to play in movie theaters in weekly installments—Flash Gordon, Tarzan the Fearless, Dick Tracy, etc.—Captain Marvel is the next link in the chain, establishing a context for the next installment of the series.

Plus, it plays with the erroneous, but culturally invasive, idea that women are too emotional to be good leaders.

Jude Law’s character Yon-Rogg and the being known as the Supreme Intelligence continually admonish Carol, Captain Marvel, to control her emotions. Emotions are discounted as weaknesses, ways for your opponent to take advantage of you. In the context of nostalgia that MC and Disney movies foster, of course such suppression of emotions isn’t encouraged by the film itself. By the end (spoiler alert, though you could probably see this coming from the moment the issue is raised), Carol learns to use her emotions rather than suppress them. They become her greatest source of power.

The movie is overly self-aware of its feminist themes, and at times seems apologetic for having the first female lead in a MU movie. Still, I think such self-awareness is better than the alternative—framing Captain Marvel through the pesky lens of “the male gaze.” Captain Marvel does its job. It links the gap between Ant-Man and the Wasp and Avengers: Endgame. It builds suspense for the coming Event. It apologizes for sexism in MU superhero culture and offers a new alternative. Plus, the movie is fun. Scenes of Samuel L. Jackson as Nick Fury and the cat Goose offer good comic relief, and Carol’s origin story fits into a clear origin-story plot formula—so we know what’s going on. Instead of focusing on tangled but intellectually engaging plot structures or deep characterization with philosophical dialogue, with Captain Marvel we can simply let our emotions engage with the film.

If you dabble with writing poems, one thing you’d learn is that the form of the poem will teach you how to read it. The same idea is basically true with movies. The first ten minutes or so will teach you how to watch the rest of the film. Captain Marvel is a film, like so many stories of this era, dripping with nostalgia, extremely self-aware, and unable to be completely judged or understood without its networked context.

Watch Captain Marvel to get amped for the next Avengers movie, or to see a kick-butt woman superhero, or just to see Goose the cat. It’s a fun film that fits right into its storytelling era. A fun film with a great soundtrack to match.

Happy screening!

—CFH

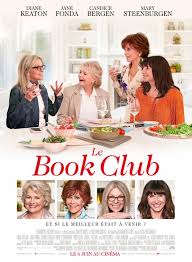

When you get free tickets to see a movie, sometimes you take chances and see something you never would have thought you’d like. Because of my work, I ended up with a free ticket to watch the movie Book Club, starring Jane Fonda, Diane Keaton, Candice Bergen, and Mary Steenburgen as four longtime friends who decide to read Fifty Shades of Grey for their book club. As you probably can imagine, plenty of ridiculousness and corniness follows as these older women begin reflecting on their lives and love lives—I although the material is pretty lowest-common-denominator, this movie manages to still be thought-provoking and entertaining. Mostly because of the extraordinary talent of Diane Keaton and her co-stars and a screenplay with great knowledge of its target audience, Book Club is one of those movies that’s just fun to watch.

When you get free tickets to see a movie, sometimes you take chances and see something you never would have thought you’d like. Because of my work, I ended up with a free ticket to watch the movie Book Club, starring Jane Fonda, Diane Keaton, Candice Bergen, and Mary Steenburgen as four longtime friends who decide to read Fifty Shades of Grey for their book club. As you probably can imagine, plenty of ridiculousness and corniness follows as these older women begin reflecting on their lives and love lives—I although the material is pretty lowest-common-denominator, this movie manages to still be thought-provoking and entertaining. Mostly because of the extraordinary talent of Diane Keaton and her co-stars and a screenplay with great knowledge of its target audience, Book Club is one of those movies that’s just fun to watch.