A week or so ago, I went and saw Wes Anderson’s new animated movie Isle of Dogs at the Conway Cinemark one lazy Sunday morning—the perfect time to take advantage of the cheap early bird ticket prices and lack of crowds. It was a beautiful day, the ground damp from light showers earlier in the morning, the sky bright blue except for a line of gray clouds gathering in the distance—the Weather Channel app predicted storms around three, though I hoped to be back home by the time they hit. I settled into my seat in the back right of the theater just as the lights dimmed and the commercials began. I was excited. Call me basic, but I’ve always loved the strange literary-ness and composed mise-en-scene of Anderson’s films—and I’m always rooting for a native Texan—but Isle of Dogs would be the first of his movies for me to see on the big screen.

Plus, who doesn’t like dogs?

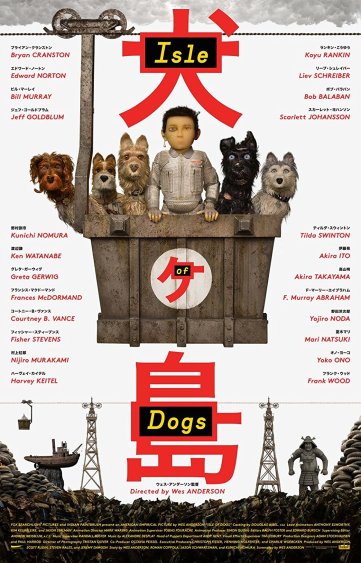

The story is set in a near-future fictionalized Japanese city called Megasaki. The mayor, Mayor Kobayashi, is determined the get rid of all dogs by sending them to Trash Island off the coast of Megasaki. Kobayashi’s ward, a young boy named Atari, flies to the island in search of his lost dog Spots. The rest of the movie is the search for Spots, with plenty of subplots and complications involving the mayor’s crooked politics and a gang of five other dogs trying to survive on the island.

If you’re a Wes Anderson fan, you won’t be disappointed by this movie. The stop-motion animation is visually interesting, and the story is imaginative yet deeply human, brimming with throwaway quirks—such as the haikus and the symptoms of “dog flu”. The movie is literate and engaging. Despite the boy Atari not being to speak English, I found myself emotionally drawn to his story.

The deepest character and protagonist was the dog Chief, voiced by Bryan Cranston. A lifelong stray, he is struggling to preserve his freedom while at the same time hoping to find a place where he belongs. Chief’s struggle is one that many of Anderson’s characters grapple with, from Royal Tenenbaum to Steve Zissou to Mr. Fox to Zero in The Grand Budapest Hotel. Chief’s struggle isn’t all that unique from those other characters. In fact, one of the main drawbacks to Isle of Dogs is that there simply aren’t that many interesting characters that take risks as far as characterization goes.

Or, rather, there are too many interesting characters, and not enough time spent with any of them. They are glossed over, left looking interesting but lacking real human depth. The gang of dogs captured my attention—and then their storyline gets forgotten as we focus on Chief growing attached to Akira. There’s a suspenseful subplot of government conspiracy (that could have gone into being social commentary, but this is a Wes Anderson movie, so nah), but the mayor and his entourage aren’t fleshed out enough for us the audience to understand their motives. Why would anyone want to persecute dogs? It feels like there has to be an easier get-rich-quick scheme than the elimination of an entire beloved species…

The biggest character disappointment was the girl Tracy Walker, voiced by Greta Gerwig. Issues of “the white savior” character notwithstanding, I found her character interesting. But I have always found it annoying that Anderson creates such tantalizingly complex and strong female characters, only to have them exist on the periphery of a male character’s story. In The Royal Tenenbaums, I wanted to know more about Margot. In Life Aquatic, I wanted to know more about Jane and Eleanor. In The Grand Budapest Hotel, I wanted to know more about Agatha. These are not the empty-headed females of many male screenwriters—they are great characters with engaging stories in their own right.

As a Wes Anderson fan, I hope one day to see a Wes Anderson movie with one of these spirited females in the lead.

And I hope that he takes more risks in his next picture, continuing his experimenting with the film form instead of falling into the trap of simply cranking out movies that match his already established style.

All in all, Isle of Dogs is a Wes Anderson movie. It’s visually beautiful, quirky, and imaginative. It’s also neglectful of good female characters and in denial about cultural issues. But every film does not exist only to make a statement. Isle of Dogs is for people who enjoy Wes Anderson’s style—and it ignores pretty much everyone else.

I myself enjoyed it, as I always enjoy the strange yet relatable worlds Anderson creates.

—CFH