I haven’t yet seen the soon-to-be released movie Ready Player One, but I did spend the last few days reading Ernest Cline’s novel. Keeping in mind the last film theory essay that I summarized on this blog (read it here), I wanted to read the book so I could then compare it to the Spielberg-directed movie once it came to a theater near me and once I could scrape together the funds for the movie ticket and some popcorn. I’m sure the movie is going to be great—and since Cline himself co-wrote the screenplay, I’m sure it’ll try to stay as true as possible to the book—but I’m just as sure that because of the different mediums, no matter how true the story is to the book the movie is going to have huge differences.

This post is basically a Ready Player One appreciation post. I loved the book and I hope that the book itself doesn’t get overlooked by the movie.

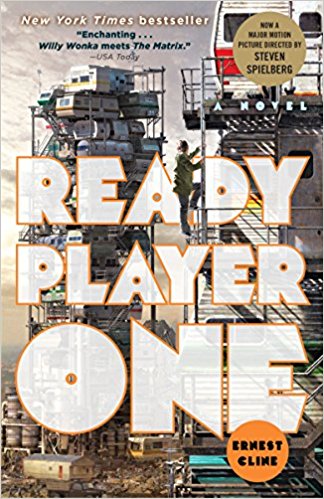

Ready Player One by Ernest Cline is a fascinating, fast-paced read. Set in the near-future, in 2044, the book follows teenage Wade Watts, a.k.a. Parzival, as he tries to find a hidden prize in the virtual reality world called OASIS. Although a great deal of the action happens in virtual reality, there are plenty of real-world consequences for Watts as he tries to get the prize—which includes billions of dollars and control over OASIS itself. What I loved most about the book was not just the tight plot or the plethora of pop culture references, but was also the fresh imagining of our future. Dystopian futures seem to be a dime a dozen at this point, and although Ready Player One is far from presenting a completely happy, utopian view of how our society will progress, the future presented in the book is one not without hope and human joy. New technology such as virtual reality is not evil, but is instead the avenue through which society and humanity will continue living and advancing. And, at the same time, the book argues that although virtual reality is not evil, it is also not reality—and, at its best, it pushes people back out into reality, into the joys and struggles of their actual lives.

The book also challenges the shaming that goes on over how people use their time with technology. There are hundreds of news stories citing doomsday statistics about tech addiction and how many hours people spend on their phones or social media or playing video games. There are sometimes stories about the craziness of people meeting online and falling in love in virtual realities. And there are hundreds if not thousands of memes shared online about the self-consciousness of people who spend a lot of time online.

At this point in our history, our culture does not value time spent online. Instead of focusing our energy on how to create a productive online atmosphere, so far we’ve been more interested in shaming people for spending time in the online realm which is, supposedly, “not real.”

But, as seen in Ready Player One, time spent in video games and the internet and in virtual realities IS life—or at least part of it. Online, people make friends, form connections, have typical life experiences, learn new things about themselves and the world, fall in love, etc. So why is that deemed “not real”? Feeling self-conscious and shamed about spending time in an online or virtual reality realm is as crazy as feeling self-conscious and shamed about spending time in any place on Earth different from where you actually live. Virtual reality worlds are really like any physical place—and going there is like going on any vacation. Stuff that happens on a vacation is completely real, completely important and meaningful.

And at the same time, no matter how meaningful, a vacation should re-energize you and push you back into your home, your actual reality.

As our society shapes and reshapes around the new technology and the Digital Revolution, we’re going to have to change some of our misconceptions about reality. I loved Ready Player One because—through detailed world-building that can only really be asserted through written text—it portrays a complex relationship with reality and technology that speaks just as much to our world today as how our world might be in 2044. These technologies aren’t going anywhere—so these types of subjects and complexities are stuff we need to be thinking and re-thinking about. So now I can’t wait to see the movie, even though I’ll probably be one of those people who read and loved the book annoyingly saying, “That’s not how it happened!” to everything in the film. Still, the story itself is worth the watch.

And I hope you’ve decided that the book is worth the read.

—CFH